Austrian Army of 1859

The Austrian army of 1859 was a large, disciplined force that embodied both the strengths and weaknesses of the Habsburg military system on the eve of modern warfare. Commanded in northern Italy by Ferenc Gyulai, it faced the combined armies of France and Sardinia during the Second Italian War of Independence.

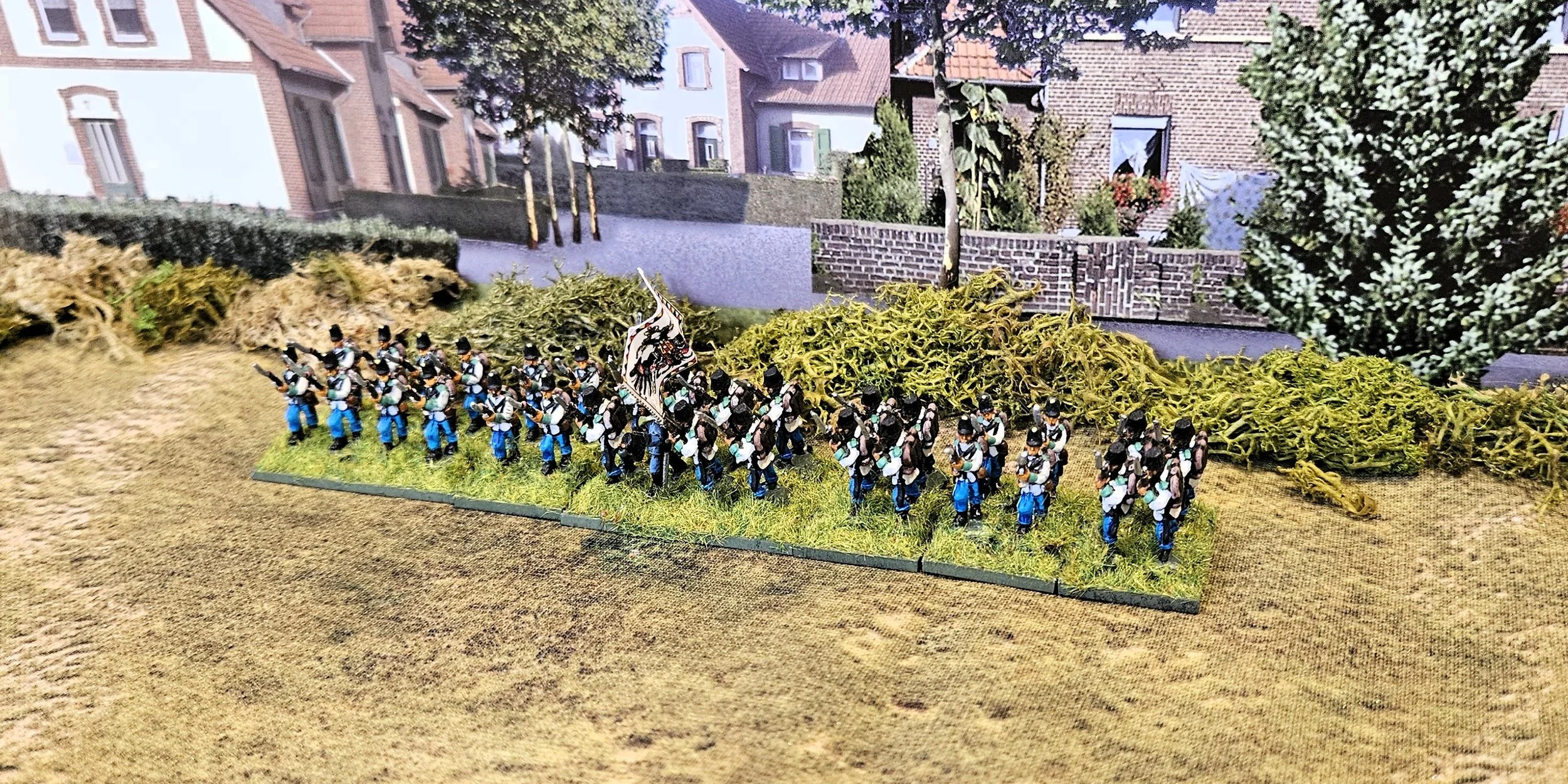

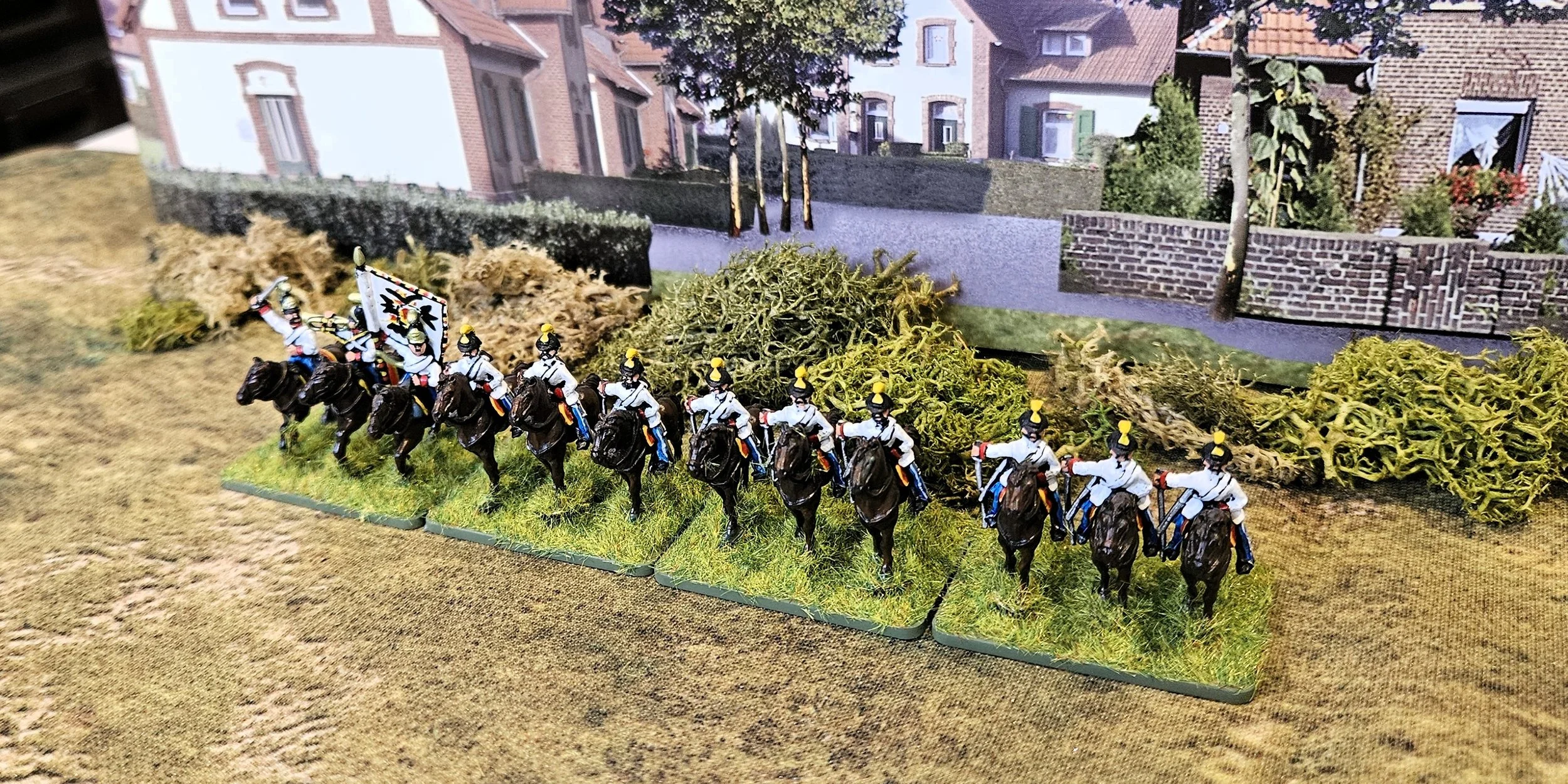

In structure, the army still relied on a multi-ethnic composition drawn from across the empire—Germans, Hungarians, Italians, Croats, Czechs, and others—united by strict discipline and centralized command. Its infantry formations were organized along traditional linear tactics, supported by strong artillery and a respected cavalry arm. Although Austria had begun to introduce rifled muskets, training and doctrine had not yet fully adapted to the increased range and lethality of modern firearms.

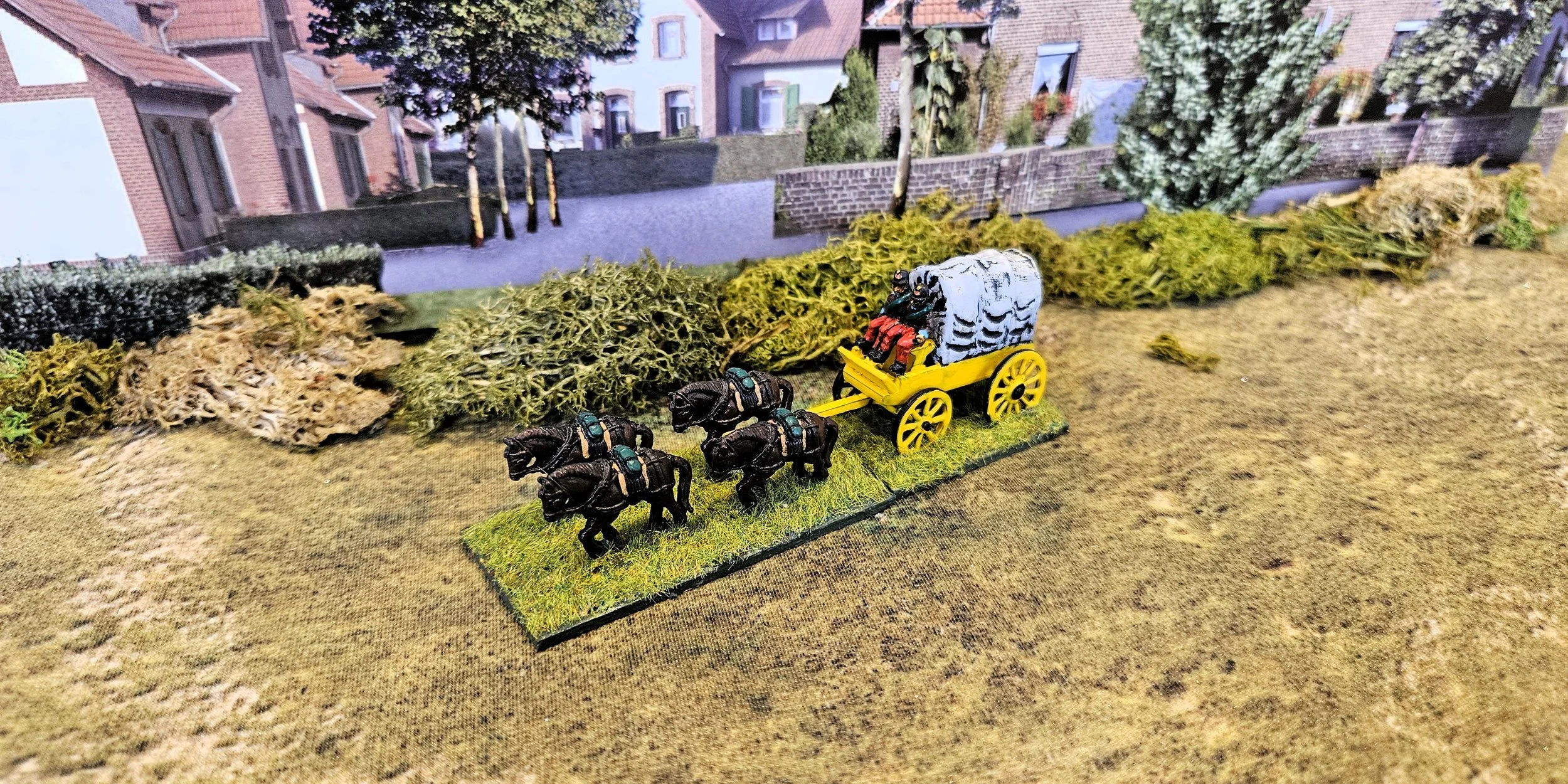

Operationally, the campaign revealed serious shortcomings. Austrian staff work and coordination were often slow, and the army struggled with logistics and communication in the field. These issues became evident in key battles such as Magenta and Solferino, where Austrian forces fought stubbornly but were outmaneuvered by more flexible Franco-Sardinian armies. The experience of 1859 exposed the need for deeper reform, foreshadowing further difficulties Austria would face against Prussia just a few years later.

Austrian Army of 1866

The Austrian army of 1866 represented the culmination of the Habsburg Empire’s mid-century military system—and its decisive test in the Austro-Prussian War. Commanded by Ludwig von Benedek, the army was still a vast, multi-ethnic force drawn from across the empire, noted for its discipline, strong artillery arm, and experienced officer corps.

By this point Austria had implemented some reforms after 1859, including improvements in organization and the introduction of rifled small arms such as the Lorenz rifle. However, these advances were undermined by conservative doctrine and slower rates of fire compared to the Prussian Dreyse needle gun. Austrian infantry still relied heavily on massed formations and shock tactics, which proved costly against modern breech-loading weapons.

The campaign in Bohemia exposed these weaknesses. Although Austrian artillery often performed effectively, the army struggled with coordination, reconnaissance, and operational flexibility. These problems culminated in the decisive defeat at the Battle of Königgrätz (Sadowa), where Prussian mobility, staff work, and superior firearms overwhelmed Austrian positions.

The defeat of 1866 marked a turning point: it ended Austria’s dominance in German affairs and forced a thorough reorganization of the imperial army, paving the way for the later Austro-Hungarian military system.